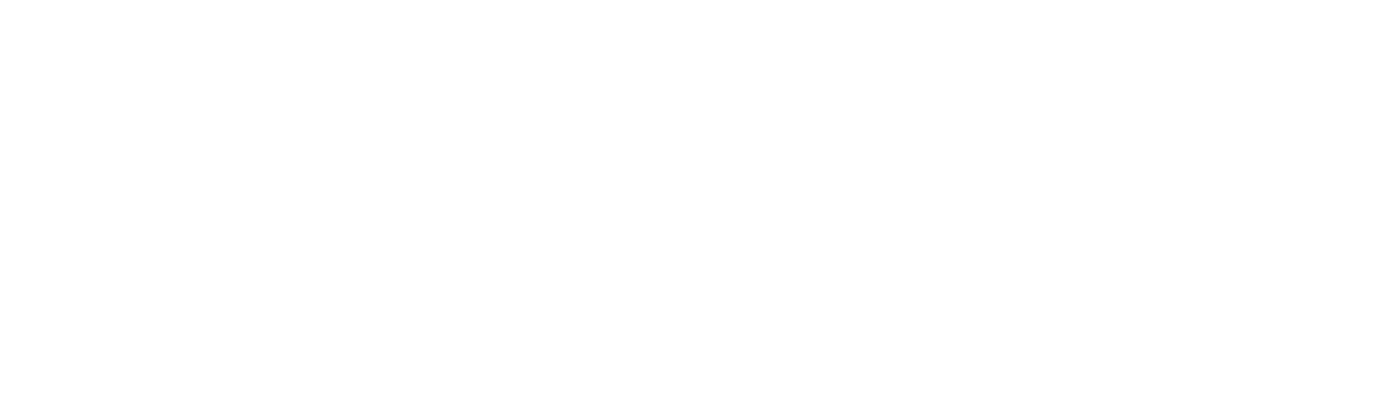

Drawings by Heyko Stöber

What does the city we want to live in look like?

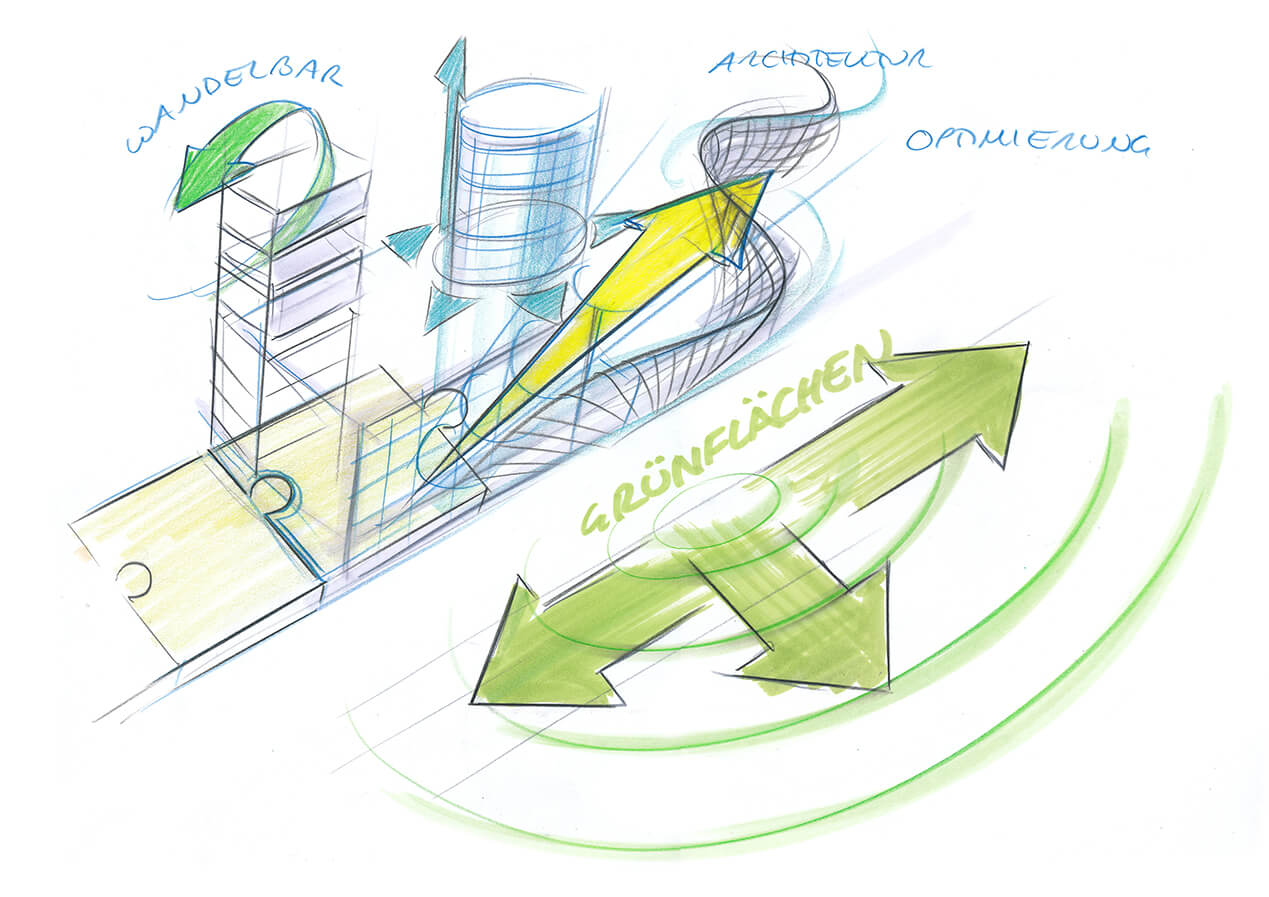

The city we want to live in is bright, green and spacious. It can adapt dynamically to the mobility, supply and accommodation needs of its inhabitants, right down to the level of individual buildings: every house can adapt to changing functions by changing its shape and architecture. The city is one for people, not for cars.

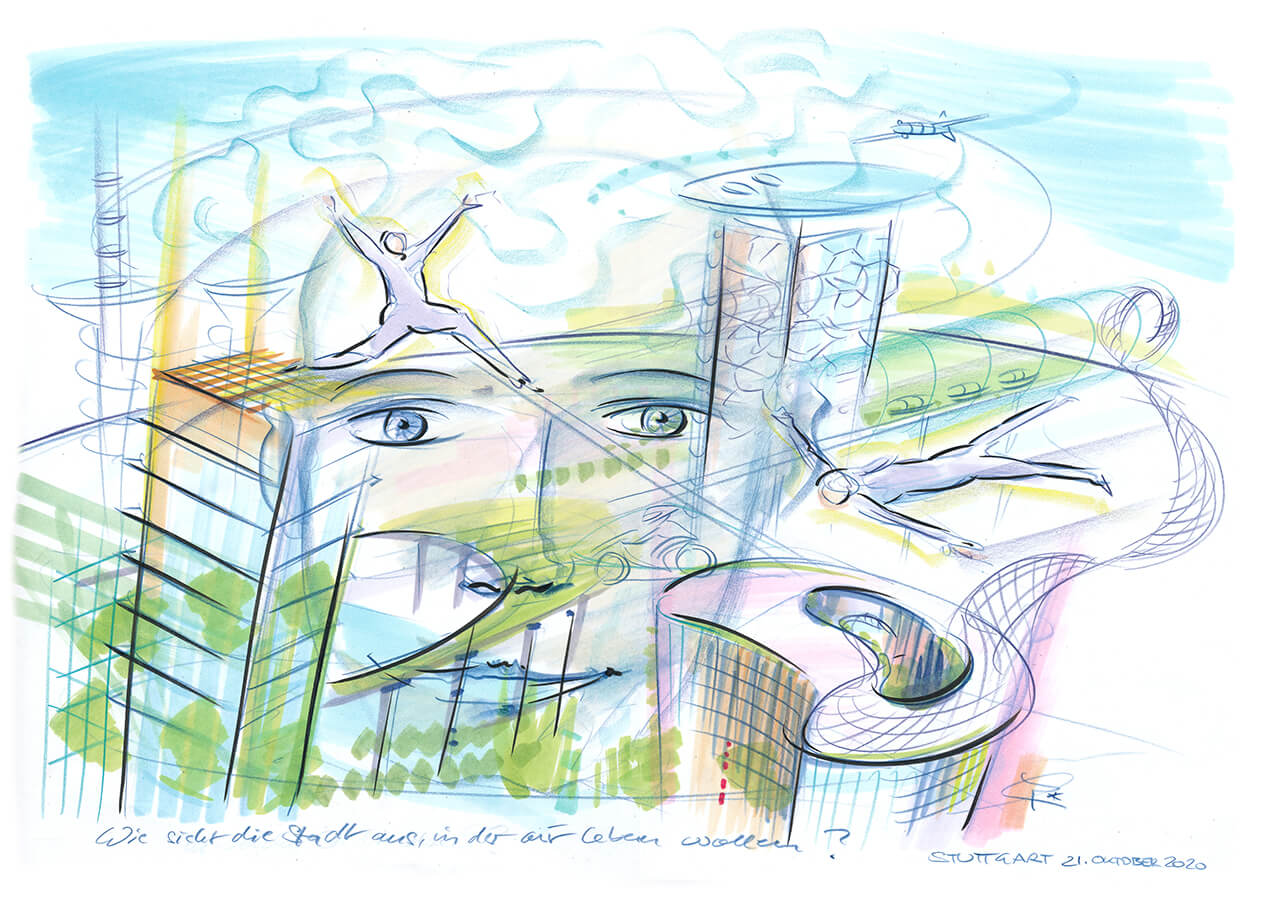

The city we want to live in is an open city. This means that moving in and out, mobility within the city (horizontally and vertically) is so self-evident that the city gate as a symbol of the border has been removed for good. There is no longer any abrupt difference between city and country, center and periphery.

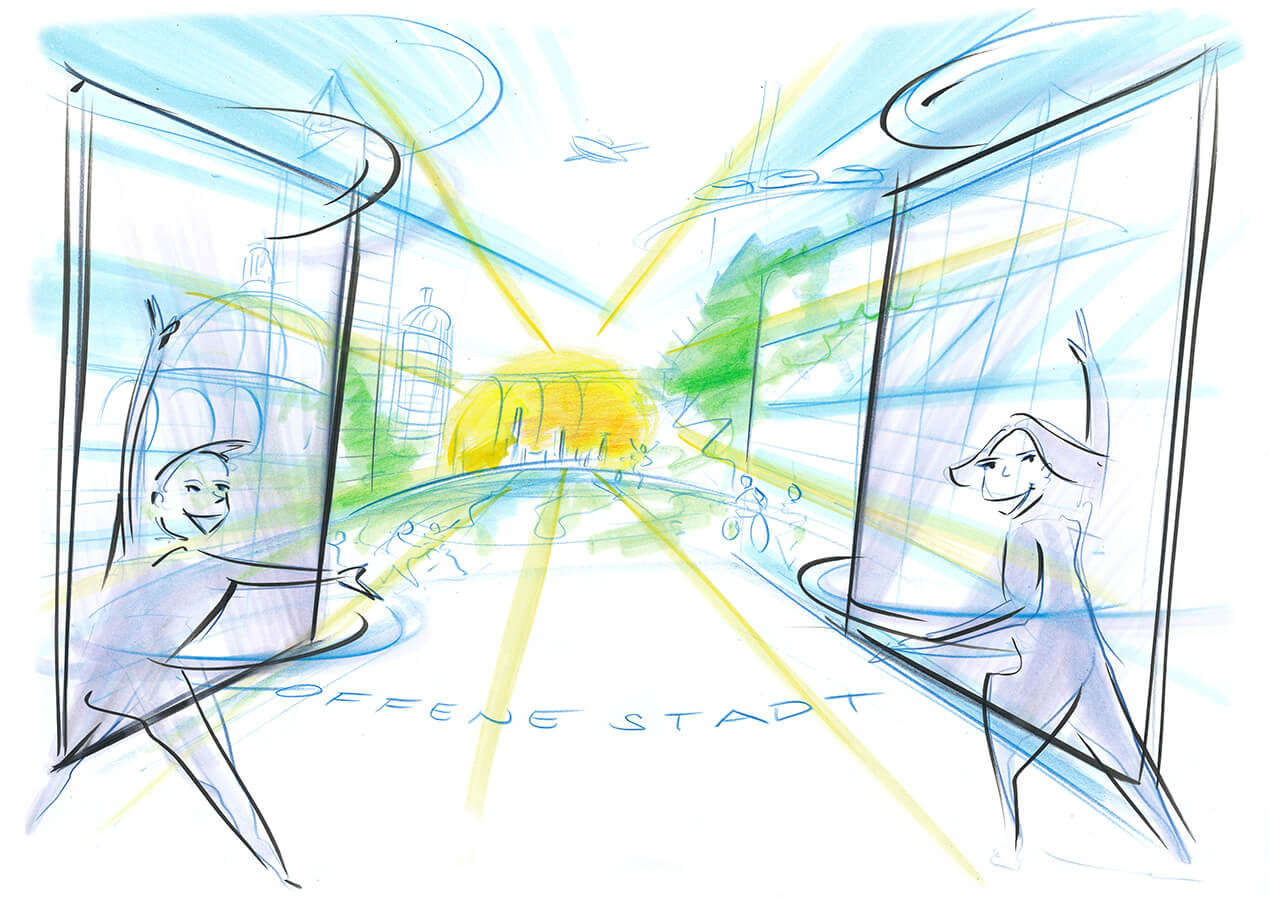

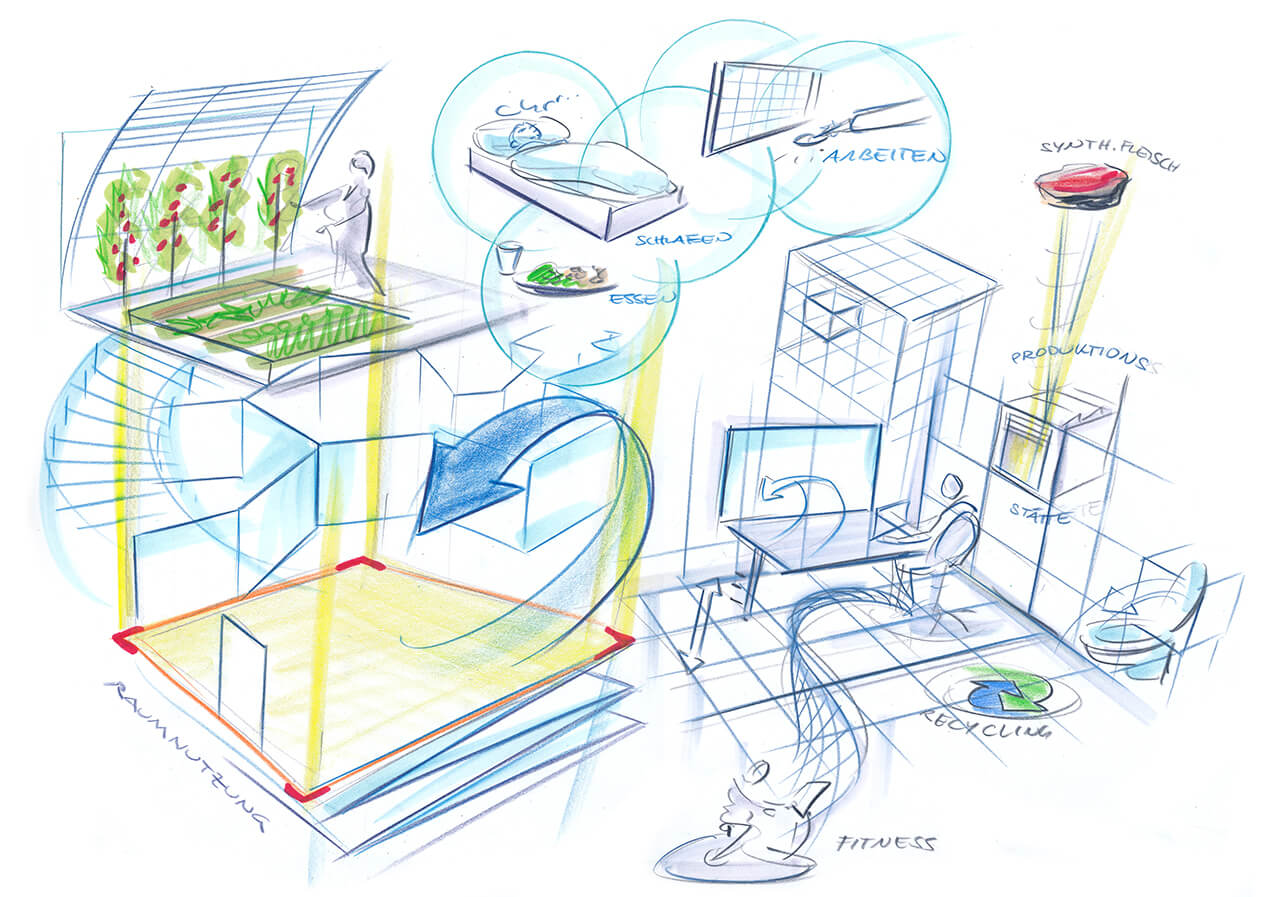

The buildings of the good city must also be changeable from within. If every apartment is to become a place of small-scale production and consumption and of recycling/upcycling directly at the point of waste generation itself, then the apartments must also be able to meet this challenge internally. Food production takes place in every apartment. Every house generates its own electricity. Every house treats its wastewater. Every house collects recyclable materials in a smart way, which are returned to production (transformation) – either locally or in larger contexts. Self-sufficiency is not desirable (because a strategy of isolation and encapsulation) – it works through participation.

The good city reduces pedestrians’ fear of other road users by radically reducing car traffic. Transportation means and planning that do not marginalize or endanger pedestrians are the rule in the good city.

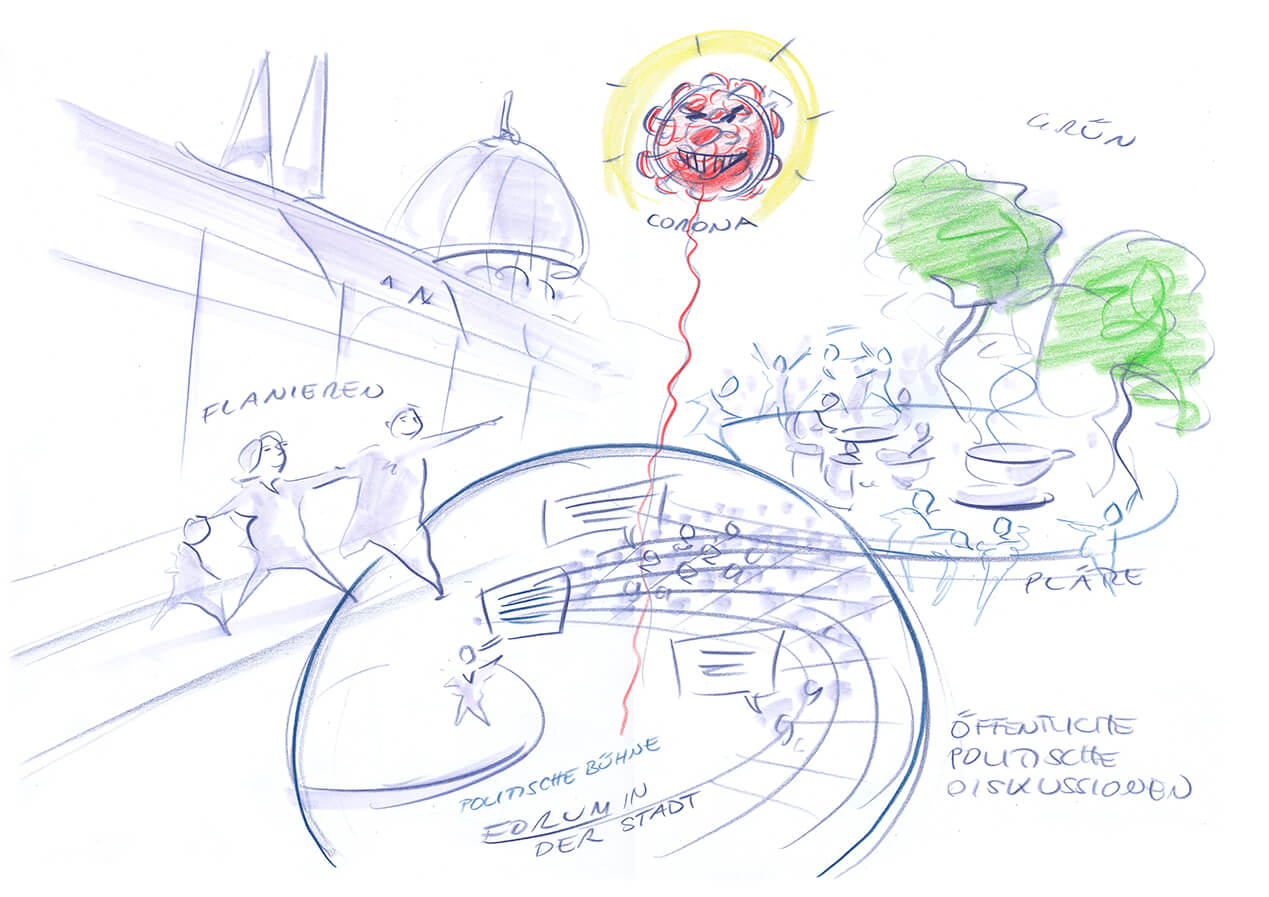

The good city recognizes that improving communication at all levels, virtual and personal, in open forums, in physical squares and in sensibly regulated virtual forums is an essential need of urban life. In a sense, the good city IS a meaningful conversation about itself by many people with close local ties.

The fact that the good city is alive can be seen in its positive attitude to strolling around. Strollers have time to literally wander through the city’s past and present. What exists today in the caring forms of the tourist “city stroll” and the odd local historian is transformed into a self-evident informing about one’s own place of residence.

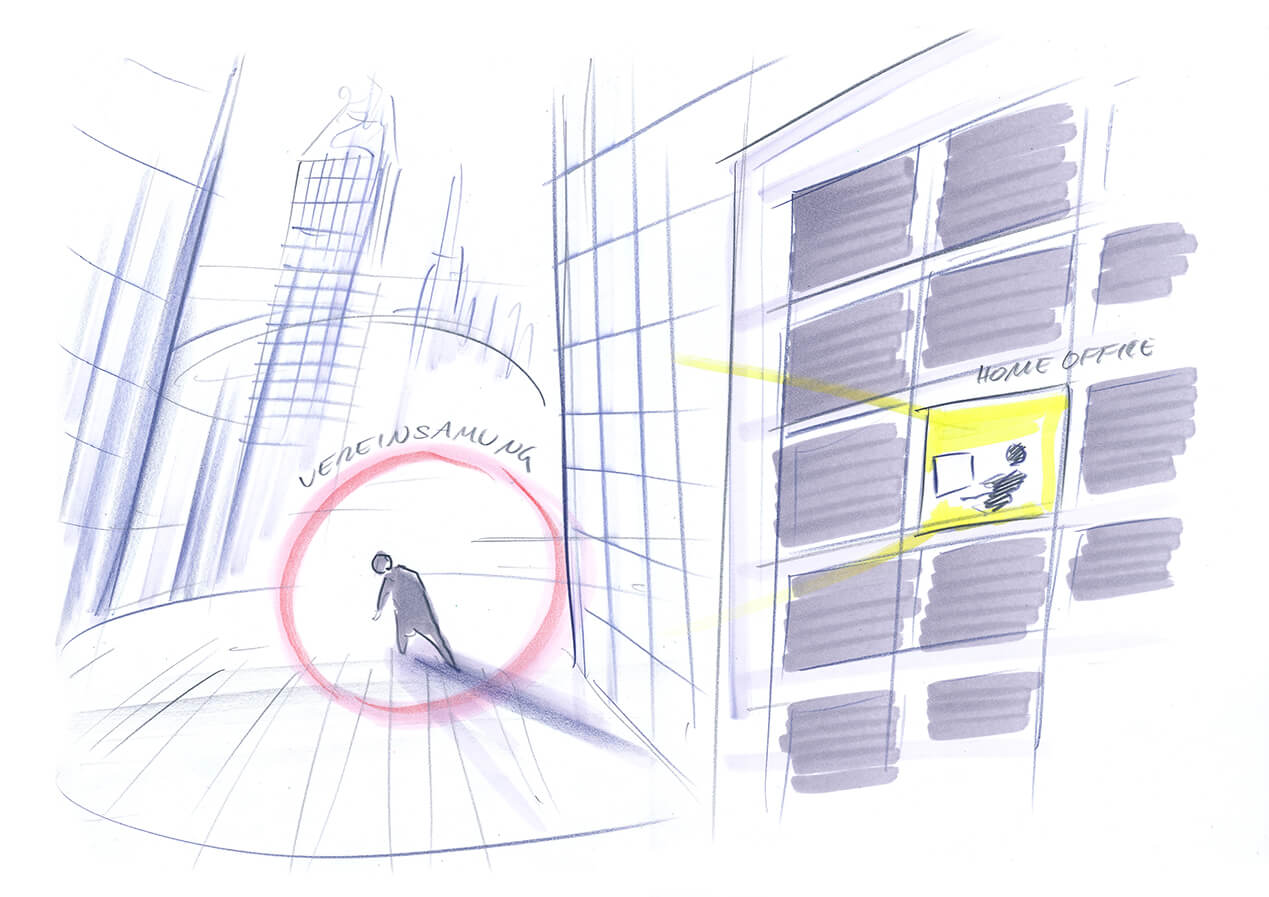

The good city recognizes that an extensive virtualization of human communication makes no sense. To counteract media-induced isolation, it creates places and opportunities for personal contact, even under difficult conditions.

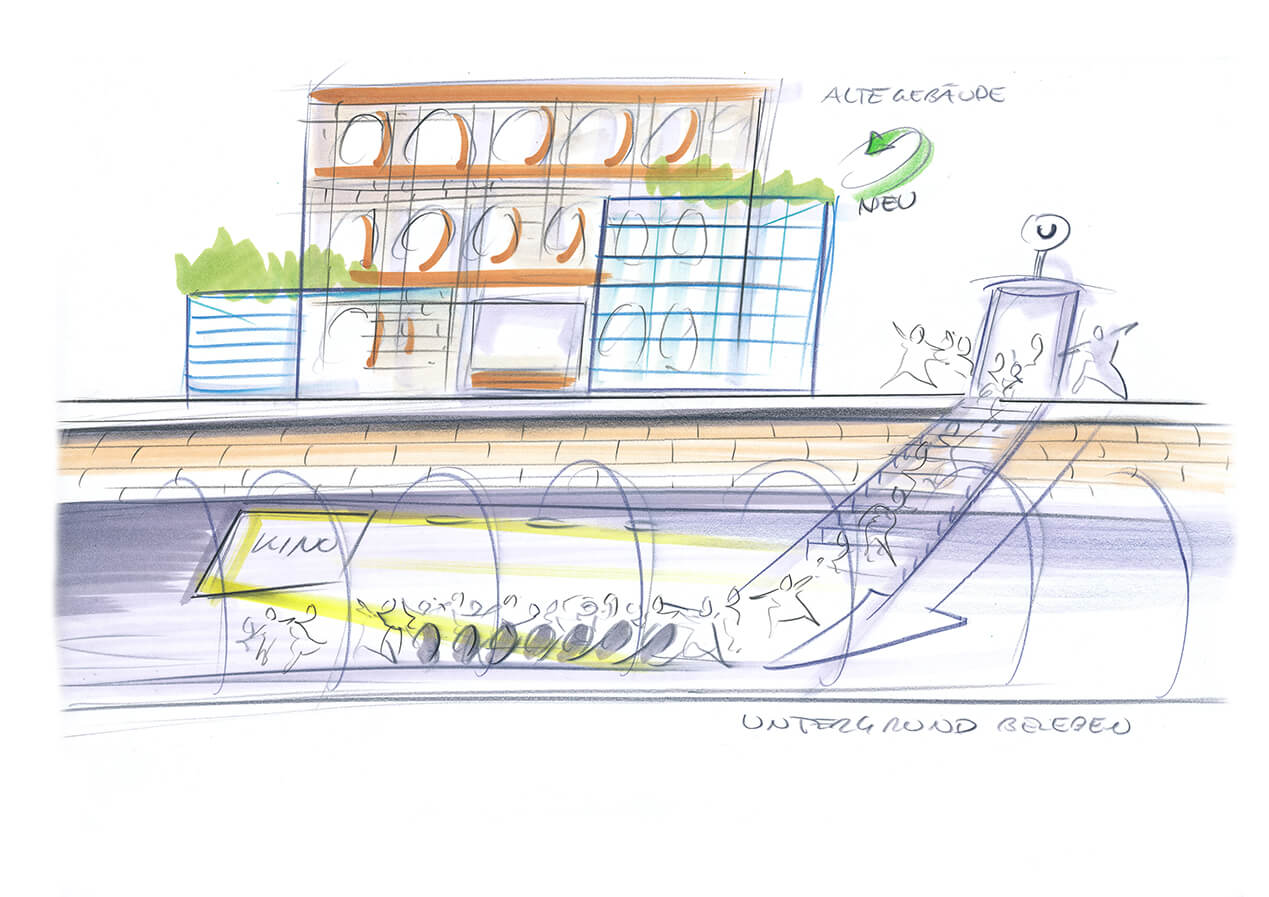

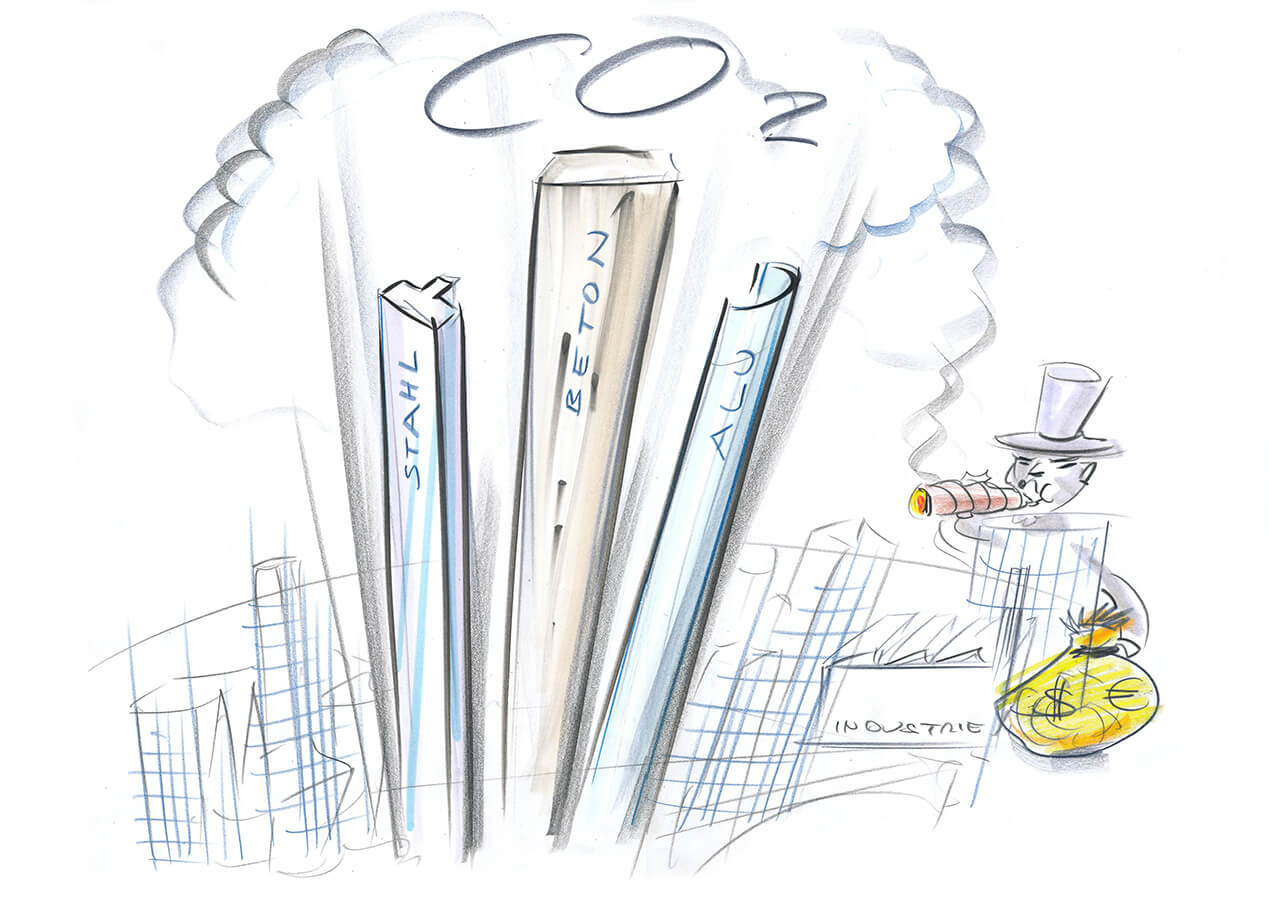

Replacing ecologically unsustainable building materials with better ones also makes sense in terms of improved social ecology. The city of the future cannot allow misplaced concrete architecture, neglect (favelas, “banlieues” and poverty ghettos) and hostile architecture to create “sick buildings” and toxic environments that are already hostile per se.

The good city enlivens the underground and more generally the hidden corners of the city. Parisian groups such as les UX with their “Untergunther” and “LMDP” departments were/are pioneers in this respect. Another example: “Stompie” in London. The hidden and the forgotten place is the place for the discovery and revival of history.

The city we want to live in is bright, green and spacious. It can adapt dynamically to the mobility, care and accommodation needs of its inhabitants.

The building materials steel, concrete and aluminum, which predominate today, are among the biggest drivers of the climate crisis in cities. For this reason alone, they must be replaced quickly.

The good city of the future is serious about recycling at a completely different level than the recycling of today. This requires new forms of recycling and up-cycling that do not take place at the glass container but directly at the consumer’s home or at least in every house.

The good city can cope with the challenge that e-commerce poses to a hitherto central function of city centers: the retail trade. In conjunction with the ideal of the open city, the retail trade mobilizes and distributes itself; goods distribution takes place de facto everywhere.

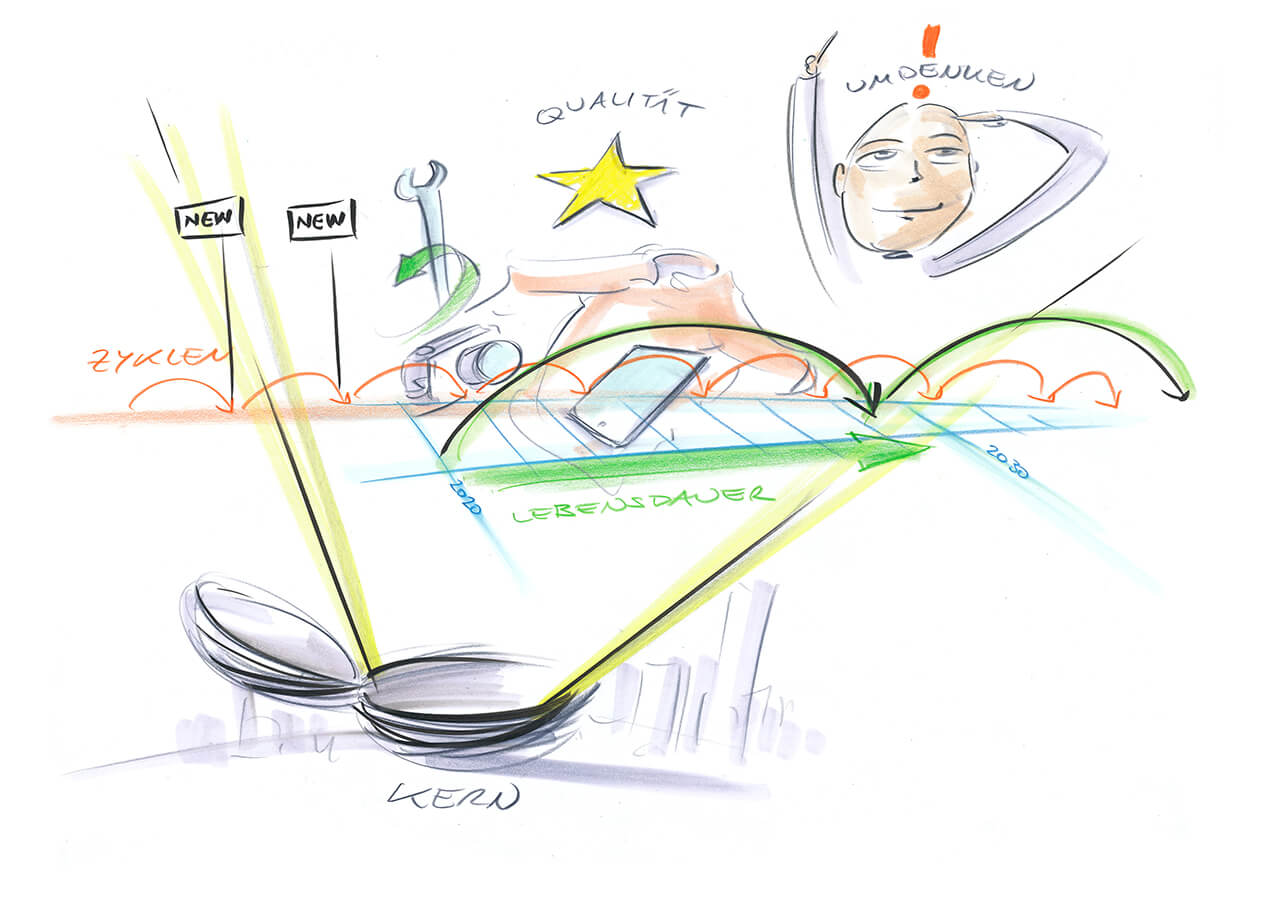

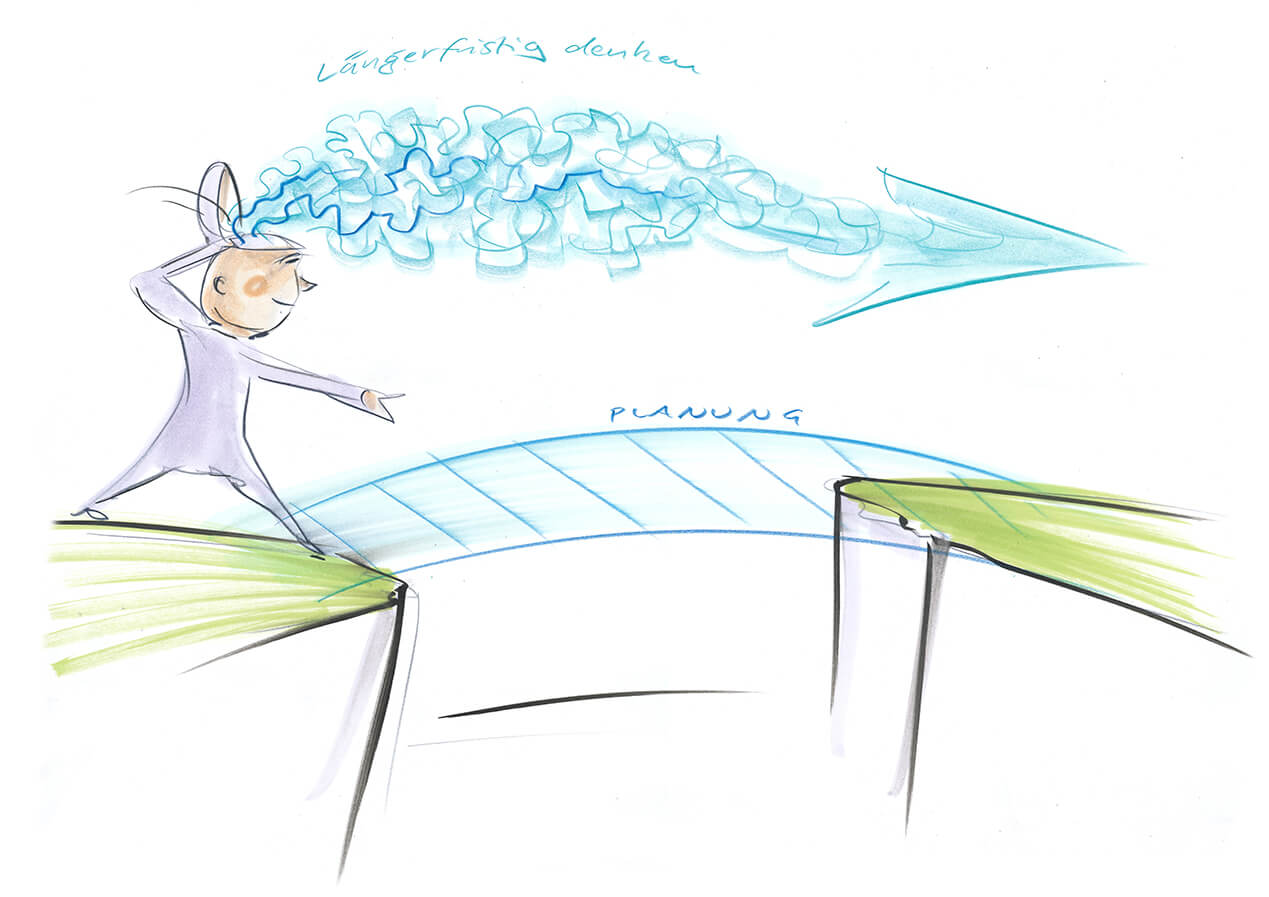

The new, good city may be agile, but it does not think strategically in short periods of time. The openness that characterizes it also means an openness to future developments that are based on good quality in the present. This refers less to the hope of eternal growth and boom (as, for example, in the misguided planning of Berlin’s sewage disposal after the fall of the Wall) than to the general prioritization of quality over quantity, of longevity over breathless innovation cycles, of recycling over new acquisition at any price. This also determines financial issues – a development that is already visible, for example, in the withdrawal of New York City’s pension funds from fossil fuels.

Security comes from prevention, early recognition of problems, and social security for city residents. Without succumbing to the illusion that it is possible to do without a security apparatus entirely, the good city socially upgrades the urban community rather than the police.